In the Land of the Mountain Maidu

In the Land of the Mountain Maidu

–Farrell Cunningham

So many things are happening here at the northern end of the Sierra Nevada mountains it seems impossible to write about them all. Two major projects continue and spring is in full bloom. The two major projects are the Susanville Indian Rancheria Weye-Ebis project and the Maidu Summit re-acquisition of lands that, for the last hundred years or so, have been owned by electric companies and most recently by PG&E.

The Language: Weye-Ebis Project (Language Persists)

The Weye-Ebis project is an effort to preserve and perpetuate the Maidu language and traditions of the north. There are two teams involved in the project and we have begun by interviewing (and recording) as many speakers of the language as possible. At this point we are more than half-way through the first year of this three-year project. Next year we will use the information we have gathered to develop a practical teaching curriculum and in the third year we will begin to implement the curriculum. We began with a list of 27 speakers. Not all of the individuals are fluent speakers but we are recording anyone who is able to speak any amount of Maidu and who learned that language from the elders. It is believed that, given the current language situation, any person who can speak even few words will add to our overall understanding of the language. People from varied family, and geographic, backgrounds will contribute to our language understanding by adding words that others might not know and also by speaking words others have spoken but adding unique family or geographic pronunciations. In these ways we will be preserving and perpetuating words and pronunciations that will enrich future generations’ vocabularies.

Not everyone we initially identified as a potential Weye-Ebis project participant has been willing to speak with us and yet we persevere where possible. We continue to add to our list as we learn of other

people who may have knowledge to contribute. Fluency is a definite challenge but not a surprise. Many of the people we are talking with have not spoken the language on a daily basis in more than 40 years.

It then becomes the challenge of the language team to attempt to awaken the language spirit within these people. Sometimes that process is painful for all involved, but it is worth the effort to create a future world in which Maidu is spoken and sung.

Some of our elders have made the Maidu language a part of their lives up to the present. I recently had the pleasure of being part of a team interviewing an 85-year-old man in Oroville. I met him nearly 15 years ago but had not spoken to him since. However, I had heard much about his efforts to preserve the Konkow Maidu dialect and I also remembered that when I had met him he had told me that his mother was Mountain Maidu. What a pleasant surprise it was for me to meet with him and discover that he has a brilliant understanding of the Maidu language, including several Konkow variations and the Mountain Maidu of his mother.

He has difficulty hearing so I let him do most of the talking and he ended up interviewing me. He asked me word after word and phrase after phrase. The more we spoke, the better his hearing seemed to become. At one point he used the word “kiki” and indicated a statue of a wolf. I answered him by saying “heleane” the word for wolf in my dialect. He took a short thoughtful pause and then replied, “Brian Hichinem was Mt. Maidu then. He said it like that.” Brian Hicihinem (name changed for anonymity) was a well-respected, Konkow Maidu, oral historian of the middle of the last century. I don’t know if Mr. Hichinem was Mountain Maidu, Konkow Maidu or both, but I do know that the elders’ ability to recall conversations, words, and circumstances was inspiring to all of us present that day.

The Land: PG&E Damages Historic Maidu Site

The other major project of the north is the Maidu Summit Consortium efforts or re-acquire lands that were formerly owned by PG&E. The lands under discussion are located in the North Fork Feather River watershed. The lands are located around Lake Almanor, Humbug Valley and along the North Fork itself.

The process began more than seven years ago when the Pacific Forest and Lands Stewardship Council was formed as a result of PG&E’s bankruptcy settlement. The Stewardship Council was given the duty of determining future ownership of PG&E lands not directly related to power production. Initially, these lands equaled more than 140,000 thousand acres located throughout California. However, through various methods, the lands were eventually reduced to approximately 70,000 acres – still no small amount.

The settlement agreement stated that the lands were to be distributed to ‘government agencies, conservation non-profit organizations, and Native American tribes.’ The lands were to be owned by these organizations with conservation easements in place and the lands were to be stewarded in perpetuity for beneficial public value. Most of the land has been distributed, but the tribes still seem to have been largely forgotten. Only one Tribal group in Southern California was able to acquire any land thus far into the process. Still the Maidu Summit continues in its efforts to acquire land.

Further, the Summit is optimistic that ownership of these lands will become a reality and the First Maidu National Park will be founded. The Park will be dedicated to a demonstration of Maidu Traditional Ecology on a landscape level in a Sierra Nevada ecosystem. Finally, the process of stewardship enacted by our Maidu ancestors will be continued on Maidu-owned land by Maidu. It is hoped that this Maidu National Park will become a place for reconnecting Maidu to the land and teaching land managers how to use methods of Traditional Ecology on other lands.

However, challenges continue. We see these obstacles as learning opportunities and also the time to demonstrate our fitness as stewards. Nonetheless, they remain challenges. In 2012, a 60,000+ acre forest fire swept through the northern Maidu homeland. Several hundred acres of land surrounding Humbug valley were affected, including lands the Maidu Summit is seeking to re-acquire. After the fire, PG&E took the fire results as an opportunity to file an emergency management (logging) plan with the California Department of Forestry (CalFire) and then proceeded to, essentially, clear-cut the forests. The “emergency” status of the plan allowed the company to circumvent most environmental laws. One law it did not circumvent was the need for, at least, five-day notification to Native American groups. However, CalFire quickly gave permits to the project and logging began on the day before any notification was received by the Native American groups. The Maidu Summit began an immediate protest, but was largely ignored.

At a meeting in January with representatives of PG&E, Forest Service, and Plumas County, after 350-acres had been logged, the Summit was finally able to raise the question of whether there had ever, in fact, been an ecological emergency. PG&E representatives insisted that the emergency was one of potential bug infestation and erosion resulting from dead trees and bare soils. CalFire declined to attend the meeting and their only comment was that the lack of pre-logging notification to the Native American groups was an emergency-induced error. No indication was given by either PG&E or CalFire that logging would be either halted or slowed.

At a meeting in January with representatives of PG&E, Forest Service, and Plumas County, after 350-acres had been logged, the Summit was finally able to raise the question of whether there had ever, in fact, been an ecological emergency. PG&E representatives insisted that the emergency was one of potential bug infestation and erosion resulting from dead trees and bare soils. CalFire declined to attend the meeting and their only comment was that the lack of pre-logging notification to the Native American groups was an emergency-induced error. No indication was given by either PG&E or CalFire that logging would be either halted or slowed.

In April of this year, members of the Maidu community were in Humbug Valley to carry out traditional activities. We noticed that the clear-cutting was horrendous and that minimal erosion control had been enacted. I also noticed that an obvious and pre-recorded Maidu village site was seriously impacted by logging activities including a landing and logging deck on the historic site and ground disturbance, down to and below bare earth, throughout the area. The Maidu Summit conducted an emergency meeting of our own the following week. PG&E and CalFire representatives were present. While we remained polite, an ecosystem was pillaged and an ancient village site had been destroyed, and so the discussion was tense.

The Maidu have, throughout history, been a polite people. We have also, perhaps because we have been polite, been an ignored people. We no longer will be classified as a small minority or “bunch of dumb Indians.” We are ready to stand up and protect our heritage, including the ancient sites of our ancestors and the ecosystem. The archaeological site boundary at the one damaged historic site was expanded, but still no indication was given by either PG&E or CalFire that the future logging activities related to this “emergency” will stop. As of this date, the Maidu Summit is making several requests: 1) that all logging activities will stop, 2) that the entire project area be evaluated for archaeological resources, 3) that the logging areas be evaluated by an independent forester and Maidu community member to determine “emergency” status and restoration needs, and 4) that CalFire laws and procedures regarding so-called “emergency” permitting be evaluated and changed to ensure that land owners (throughout the state) can no longer use this process to circumvent environmental laws as well as social responsibility.

I am not sure what the future holds. At the April meeting, the PG&E forester thanked me for the professionalism of the Maidu Summit. I suppose he meant that we spoke clearly and coherently in the outline of our issues and concerns. We also did this at the January meeting, but we were ignored. We will continue to maintain our professionalism, but this word will mean maintaining our integrity and the integrity of the land in so far as we understand each of these things, and in respect to our ancestors, human and non-human relations, and the future for all.

It is not the Maidu Summits intent to offend anyone. If any offense is taken it will be well to understand that we did not create this situation. It is my hope that, once mistakes are acknowledged, all parties involved can, and will, work together to create solutions that will ensure none of us will find ourselves in a similar situation again.

Wild Plants of Spring

Here in the north, Spring is in full swing. I have been enjoying various greens such as ‘wadakdaku’ miners lettuce which I prefer raw, and ‘puku’ a small plant that has greens that taste like cilantro and modest yellow flowers. This plant I enjoy fresh and cooked. It is delicious added to scrambled eggs. I don’t know the English name. I recently went with some relatives to a high mountain spring where we gathered heaps of ‘mom sawi’ watercress. Cooked or fresh, the spicy flavor is a springtime favorite.

The optimum time for gathering Willow (for making baskets) is quickly passing. I gathered several hundred stems, so far, which I delivered to an old lady in Indian Valley (Plumas County). She makes fine baskets.

I went with some relatives over to the Lake Almanor area and gathered Chokecherry stems, also for baskets and arrows. The flowers of the chokecherry are now fading but they still smelled so delicious. While the flowers are sweet the bark tends to be an acquired scent and the stems should be gathered before flowering. And now, into the spring…….

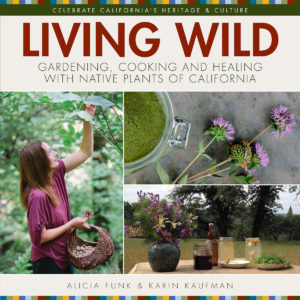

Note from Alicia Funk: If you would like to help preserve Humbug Valley according to the methods of Traditional Ecology, please become a friend of Humbug Valley and donate to: http://www.maidusummit.org/friends-of-humbug-valley/.