Meadow Restoration

Pulum Koyo: Year 1800 and 2011; Future To be Determined

(Pulum Koyo means Grinding Rock Meadow in the Maidu language)

Late Summer 1800; Pulum Koyo.

Singing softly, a woman, ceanothus and redbud pack basket beside her, uses her mahogany digging stick to pry the papam tubers from the ground. Later she will string them and dry them for winter use. Sun dried yellow grass stems, from which earlier in the season the seeds had been harvested, mix with the bleached stems of brodiaea and contrast with the greens of sedges, deer grass, and herbaceous plants in the riparian areas. Late- flowering papam, white and soft, offer further contrast, in patches and singly, among the various dried stems whose season of fruiting has passed. A grass stem quivers beyond the effect of wind where a small bird clings to it pecking at the residual seeds.

Along the meadow edge other women snap off the heavy bunches of elderberry and grape while, overhead, squirrels chatter and bound from branch to branch among the giant oaks. Two squirrels chase each other down the entire length of the meadow and out of sight without touching the ground. A hawk watches them from atop a towering pine while woodpeckers huddle together on a branch of a shining grey snag watching the hawk.

A man, sitting in the meadow near the acorn pounding rock his wife uses, looks uphill beyond the meadow edge and through the openings between the giant tree trunks toward a sun illumed forest opening in the distance. Deer are browsing there. He uses his oak wood shuttle to weave a milkweed fiber headnet that he will wear at the upcoming Fall harvest ceremony. Beside him lies a newly completed fish net made of the same fine and strong material. He is silent but he is praying in his own personal manner. Like the others of his community, he understands that the thoughts he puts into these objects and the world around him will ultimately form those things even more so than will his hands and actions.

Spring 2011; Pulum Koyo.

Sounds form the setting as much as the view. There is the gentle rustling of oak leaves, the twitter of small-bird song interspersed with the raucous chai-yit, chai-yit of scrub jays. White noise, an airplane and distant traffic underlie all.

Young pines mingle with deer grass where a spring forms a small marsh on the western meadow edge. The head of the spring, obscured by a bisecting road, hidden among brush, fallen trees, and a thicket of standing trees, offers flowing water even in this dry year. It appears that, at some point in the past an effort was made to develop the spring in attempt to increase flow and create watering points for livestock.

A raven flies over the meadow. A hawk cries out in the distance. There is the invigorating scent of fallen pine needles baking in the sun beneath the young pines that are thrusting up into the canopies of the oaks that are their elders. The oaks stretch their limbs as they reach for the increasingly obscured sunlight. Roads are in view, likely following the original gentle footsteps of Maidu but hardened now by the tracks of ‘progress.’ A squirrel, searching for palatable young greens, skitters across a thick layer of dried leaves that are slowly choking out his nutrient source. Lizards sound larger than life as they chase each other through the same. To the east of the meadow large Manzanita brush has been removed allowing for the glimpsing of not so distant ridges across the river canyon. Already the next generation of brush is growing. Hundreds of small Manzanita are present, only a few inches high this year, but soon to take on the role of dominant understory vegetation as their progenitors had done only a couple of years previous.

To the south young grey pine, oak, and brush dominate the landscape. The view north and west is obscured beyond meadow edge by the same vegetation although the trees there are older and larger -all meld together to create an aesthetic symbiosis. The meadow is smaller than in years past and the corridors connecting it to the series of other meadows and forest openings are largely blocked by brush. Nonetheless, the meadow endures, in part, because the wetness of seasonal seeps and year round springs does not allow for forest tree species to germinate or, once germinated, grow to any great size. Yet, though the meadow exists in form, its composition of grasses and herbaceous species has changed greatly in the past two centuries.

Native meadow grasses are virtually non-present. They have been replaced by newcomers in the forms of short grasses and aggressive herbaceous plants. The burs seem to take predominance but, perhaps, the impression is only derived from their insistence upon clinging to hair and clothing and thereby forcing notice. Brodiaea stems, like their ancestors, stand bleached in the sunlight.

A large oak bows to the meadow. Still living upper limbs support its trunk on the northwest meadow edge. A young Douglas fir, caught in the root upthrust, changes shape as it strives to regain an upright posture.

A bobcat meanders through the meadow and comes to sit upon the grinding rocks that have long remained unused. The ancient humans of the land are gone from this place. None-the-less, the bobcat has the opportunity to look upon a man who looks back at it.

-Farrell Cunningham, Mountain Maidu

Pulum Koyo (Grinding Rock Meadow) Restoration Plan

By David Jaramillo (Whole Earth Forestry) and Farrell Cunningham (Mountain Maidu)

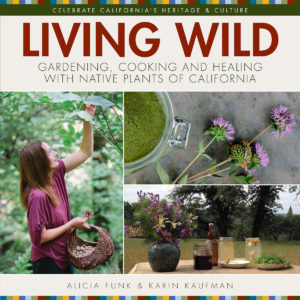

Farrell at Pulum Koyo (Grinding Rock Meadow)

The meadow and surrounding ecosystem will be re-invigorated through a combination of thinning, pruning, seeding, burning, traditional resource procurement methods, singing, talking, and prayer along with adaptive methods as necessary and appropriate. Special emphasis will be placed on maintaining, enhancing and creating ecosystem-wide species diversity of flora and fauna. For example, wildflowers will thrive as the increased sunlight, following overstory thinning, feeds energy into their cells and fires stimulate their growth and enrich the soils upon which they depend. Squirrel, deer, and other fauna populations will increase as new palatable greens become more available.

Over time we can expect many positive changes to the meadow ecosystem. Removal of encroaching trees and shrubs, especially surrounding the spring, will result in a larger meadow and increased understory vegetation abundance and diversity. It is anticipated that following a season of “underburning,” planting of native seeds, and re-establishing native vegetation, the meadow will begin to resemble a flower-based patchwork quilt of magnificent colors. Also following burning and thinning, riparian vegetation will begin to spread further into the meadow as spring output increases.

Primary Goal: To restore the land to a condition similar to what it would have resembled in the year 1800 utilizing the philosophic thought patterns of the Maidu as exemplified through Traditional Ecological Knowledge. This goal will be achieved through an adaptive landscape stewardship and restoration process focused on long-term sustainability and maintenance.

Guiding Principles:

- Take care of the land and the land will take care of you

- Humans have been and can be again positive contributors to the ecosystem

- Humans are part of the ecosystem

- All other ecosystem components are people too

- Thought patterns affect ecosystem restoration outcomes

Objectives:

- Increase wildlife habitat diversity Increase native plant diversity, vigor, and abundance

- Reduce invasive species

- Minimize wildfire risk(s)

- Increase water/spring output(s)

- Increase overall land base health and ecosystem function

- Reintroduce controlled burning of underbrush

- Maintain function and increase meadow size

- Grow abundant native plant foods, basketry and tool making materials

One comment on “Meadow Restoration”

Comments are closed.

Hello

Feather

Friend,

Flicker.

I remember you.