The Case for Native Food Crops

This is an excerpt from an upcoming article to be published by the Rachel Carson Center for World Food Day, October 2013. -Wild Local Food, Alicia Funk

Although “nature” is a word used commonly with reverence, much of our real, daily connection to the natural world has been lost. With a changing climate, a 75% loss in food diversity over the last century, the introduction of patented, genetically modified food (GMO’s), and the decline of cultural knowledge of the food uses of native plants, humans are now in a nutritionally vulnerable position.

In the last century, we’ve switched from eating an abundance of local plant varieties, with 30,000 edible species worldwide, to only consuming a narrow range of high-yield species, which, in many cases, lack the taste and the nutritional content of what we enjoyed a hundred years ago and whose cultivation requires significant environmental resources. According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), 95 percent of the food humans consume comes from only 30 crops, with the majority consisting of rice, wheat, maize, millet, and sorghum.

Food localization means cultivating a sense of place—a deep awareness of the land we call home. It is a process that depends upon science and traditional indigenous knowledge as well as the continuing exchange of new ideas on sustainable interdependence within the native habitat.

An increasing number of American consumers have demanded access to sources of food that benefit their own health and the wellbeing of the environment, as indicated by the growth in the organic food and beverage industry from $1 billion in 1990 to $26.7 billion in 2010.

Individuals interested in the movement toward wild food include a range of diverse communities—local food enthusiasts wanting sources of fresh, community-sourced food, “foodies” looking for an exotic taste adventure, gardeners wanting to grow drought-tolerant plants, organic food advocates interested in new foods that are pesticide-free and vitamin-rich, environmentalists concerned with climate change, individuals worried about the potential “end of the industrialized world,” and advocates for conserving cultural knowledge.

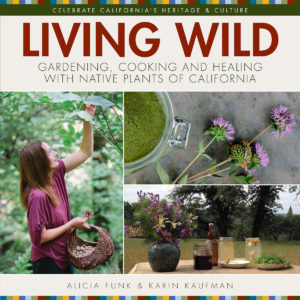

Native plants, especially the wild ancestors and closely related species to those in commercial commerce, have the potential to provide significant nutritional benefit to local communities. In Europe, approximately 65% of the 2,000 plants traded commercially are natives and 90% of these species are still collected from the wild. Each region should compile a list of native crops with the potential to provide food independence, along with traditional knowledge of timing of harvest and processing methods, current phytonutrient analysis and growing methods. Projects are currently underway by the Living Wild project to provide this community database for the Western region of the United States, and the Millennium Seed Bank and the Global Crop Diversity Trust are working to gather the wild relatives of 29 key food crops, conserve them in gene banks, and then breed new varieties adapted to climate change.

There are several limiting factors that need to be addressed in order to integrate native, wild foods into the local food movement. Widespread use by communities depends upon successful cultivation, sustainable wild harvesting methods, efficient processing methods, additional scientific research and consumer education.

Declining diversity and nutritional content in commercial food crops, loss of genetic control of food from the hands of farmers to the intellectual property of multi-national corporations, disappearing indigenous knowledge systems and difficult to predict climate changes, make it imperative to encourage regional, wild food sources, through cultivation and sustainable wild harvest. With a collaborative approach designed to share information and resources, communities can grow and gather nutrient-dense food crops that protect biodiversity and cultural heritage, while bringing families back outside.