The Manzanita Report

Manzanita Ecology by Rachel Durben of Sierra Streams Institute, rachel@sierrastreamsinstitute.org.

Introduction by Alicia Funk. Manzanita has captured my interest and heart and I’ve used it more consistently over the past several years than any other wild plant. Most people don’t like it and consider it a fire hazard. However, in a healthy forest, it provides an essential function for the landscape, birds, wildlife and humans. It helps stabilize the soil and provides delicious, edible flowers in the late winter and berries in the summer. There are seven primary species with many subspecies in the Sierra Nevada, which are an abundant part of the chaparral landscape. August is the perfect time to collect the berries, which are ripe when they are dark red in color. Here is the basic recipe for enjoying Manzanita berries and I hope you will learn as much as I did from this report by Rachel Durben, a scientist at Sierra Streams Institute.

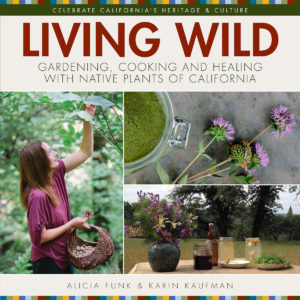

Basic Manzanita Recipes: Antioxidant Sugar and Cider 2 cups berries = ¾ cup sugar. Make sugar by grinding berries on medium low in food processor or blender for two minutes. Use a wooden spoon to press crushed berries through mesh strainer and into a bowl. To make the cider, simmer the leftover seeds and skins in 12 cups water. Simmer for 20 minutes and then strain. Keep refrigerated and drink cold or hot. Note: Manzanita berries are 3 times higher in antioxidants than blueberries. See the Living Wild book for cracker and muffin recipes!

Manzanita Ecology

- Genus Arctostaphylos

- 106 total species, ranging from southern British Columbia to northern/central Mexico; 95 in California, 7 in Sierra Nevada (with several subspecies of each). [1]

- Many coastal species are endangered or rare, primarily due to small ranges and heavy development; 3 species in the Sierra Nevada (A. nissenana and A. myrtifolia are species of conservation concern, A. manzanita -5 of 6 subspecies- rare throughout range) have very small populations and very particular growth requirements. [2]

- The rarest species are: A. hookeri ravenii (Presidio manzanita) with one individual discovered in 1951 in the Presidio by Peter Raven and since successfully cloned; and A. franciscana, which hadn’t been seen in the wild since 1947, but was discovered in 2009 in the Presidio and has since been transplanted and preserved. [1]

- Common name, manzanita, means “little apple” in Spanish, a reference to their tiny apple-like fruits.

- Drought-tolerant evergreens.

- Commonly used as erosion control due to low-growing, spreading growth form and extensive root development. [3]

- Extensive mycorrhizal associations allow growth in nutrient-poor soils [3]

- Threats: development/loss of habitat, fire suppression (inhibits germination of seeds) and subsequent extreme fire events will destroy populations of most species, pathogens (root rot is a major problem- greater than fire –for A. myrtifolia) can spread rapidly among dense stands. [3]

Life history

- Can live for >100 years [2]

- Reproduce sexually (by seed) and asexually through root or burl sprouting (some species). [2]

- Most species become sexually mature (produce flowers and fruits) by 10 years of age, and all are polycarpic perennials (do not die after fruiting). [2]

- Flowering in Sierra Nevada occurs from winter until early summer, depending on elevation. [2]

- Seeds dispersed from late summer until the following spring and can remain dormant in the soil for hundreds of years. [2]

- Seeds require scarification from heat (fire) or another disturbance (scouring over rocks or other substrate, passing through animal gut, etc.) to weaken the seed coat and induce germination. [2]

- Sierra Nevada species are adapted to high temperatures, low soil moisture, and are generally shade intolerant. Excessive shading of seedlings (in closed canopy forest, for example) will kill most species. [2]

- Episodic recruitment (usually due to fire event or other disturbance) with low long-term survival rates. Often very dense stands in first 5 years, but naturally thin out over time. [2]

Role in ecosystem

Fire Ecology

- Early colonizers post-fire [2]

- Seeds of most Sierra Nevada species will germinate after disturbance such as fire, and dominate the landscape for decades. [2]

- Some species fire-adapted (will resprout from underground burl after fire), but some killed by fire. [2,3]

- High drought tolerance and prolonged fire suppression results in overgrown stands that are highly flammable. [2,3]

- USFS and California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection recommends selectively removing dead & dying manzanita to reduce the amount of fuel available and reduce fire frequency and intensity in areas of concern.

- Clearing spaces between large trees and shrubs mimics pre-settlement landscape created by periodic burning from lightning and occasional fires set by Native Americans. This clears out brush and saplings, which opens up meadows and also breaks up the “fuel ladder” where fire jumps from grass to brush to the tree canopy, creating high heat, high intensity, large-scale burns. [4]

- Manzanita’s natural drought tolerance means that even healthy-looking plants don’t typically hold much moisture and therefore can be highly flammable. Removing dead branches and keeping live plants well-watered with ample spacing between stands or individuals (at least 10 feet in flat areas and 30 feet in steep areas) can reduce the fire risk. [4]

- Repeated, short-interval fires will eventually eliminate the persistent seed bank. [2]

Animal Interactions

- The fruit is eaten by black bear, deer, coyote, birds, rodents, and humans. [5,6]

- Deer will browse seedlings up to 3 years old following post-fire germination, but the mature foliage is considered unpalatable to animals. [6]

- Birds and mammals disperse seeds. Softening of the seed coat in the gut of animals aids in germination. [6]

- Insect (mostly bee) and humming bird pollinated. [7]

Ecological Adaptations

- Manzanita are early colonizers after fire due to their fire resistance and reproductive adaptations (some species resprout after fire and have seeds that will germinate post-fire). [2]

- Most are not shade-tolerant, so grow well in open spaces such as chaparral, ridges, steep slopes, and woodland edges. Shading by mature conifers and deciduous trees confines them to these areas in later successional stages (when trees become large enough, manzanita will only persist in open sections of the forest, on exposed ridges, or in chaparral environments). [2]

- Plants tend to have short (<6m) growth form and intermittent to continuous canopies, allowing them to colonize exposed, harsh environments. [2]

- High drought tolerance and fungal symbioses allow growth in nutrient-poor, xeric conditions. [2]

- Fire suppression results in large tree encroachment (seedlings not killed by fire) that can cause manzanita to decline in numbers by shading out mature plants and preventing germination of fire-adapted seeds. [2]

- Some Sierra Nevada species, such as the abundant Greenleaf and Whiteleaf manzanita (A. patula and A. viscida) have allelopathic properties, with leaves that contain chemical compounds that are detrimental to the growth of other plants when they decompose in the soil. This prohibits the growth of competing species and encroachment by conifers. [2]

- Despite being drought tolerant, Sierra Nevada species tend to have low water use efficiency, depleting soil moisture and inhibiting the growth of Ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, and other seedlings. [2]

Human Interactions

- Historically, Native American tribes in the Sierra practiced a regime of frequent, low-intensity burning, pruning, sowing, tilling, and selective harvesting to manage the ecosystem and increase production of desired plants. Frequent burning of manzanita and the chaparral and woodland environments in which they most often occurred stimulated shoot growth, increased berry production, induced seed germination, and eliminated dead growth that could lead to high-intensity, damaging fires if left to accumulate. [11]

- Since the early 1800s, when European settlers began moving into the Sierra Nevada, a history of fire suppression has resulted in some landscapes becoming overgrown and more susceptible to high-intensity, large destructive fires. Elimination of regular small-scale burns was enforced until recently, but the benefit of moderate ecosystem management is now being recognized and the land ethics and practices of Native Americans are being studied and implemented in many modern land management plans. [11]

References

[1] Fimrite, Peter. Manzanita bush’s discovery excites scientists. San Francisco Chronicle 12/26/09.

[2] Sawyer, J.O., Keeler-Wolf, T., and Evens, J.M. 2009. A Manual of California Vegetation, Second Edition, California Native Plant Society Press, Sacramento, CA.

[3] Flora of North America, www.eFloras.org FNA Vol 8 [Accessed 1/23/12].

[4] McDougald, N. and D. Neilsen. Fuel Reduction and Fire Protection. Coarsegold, CA Resource Conservation District, www.crcd.org [Accessed 1/28/12].

[5] Hitchcock, C.L., A. Cronquist, and M. Ownbey. 1959. Vascular plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part 4: Ericaceae through Campanulaceae. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 510 p.

[6] Sampson, A.W., and B.S. Jespersen. 1963. California range brushlands and browse plants. Berkeley, CA: University of California,Division of Agricultural Sciences, California Agricultural Experiment Station, Extension Service. 162 p.

[7] USDA, NRCS. 2012. The PLANTS Database, http://plants.usda.gov [Accessed 2/20/12). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

[8] University of Michican- Dearborn, Native American Ethnobotany Database. http://herb.umd.umich.edu/ [Accessed 2/21/12].

[9] Bond, Owen. 2006. Herbal remedies with manzanita bark. www.livestrong.com/article/366102 [Accessed 2/21/12].

[10] Mills, Simon. 1994. The Essential Book of Herbal Medicine. USA, Penguin Books. 704 p.

[11] Anderson, M.K., and M.J. Moratto. 1996. Native American land-use practices and ecological impacts. Chapter 9 in Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: final report to Congress, vol. II, Assessments and scientific basis for management options. Davis: University of California, Centers for Water and Wildland Resources.